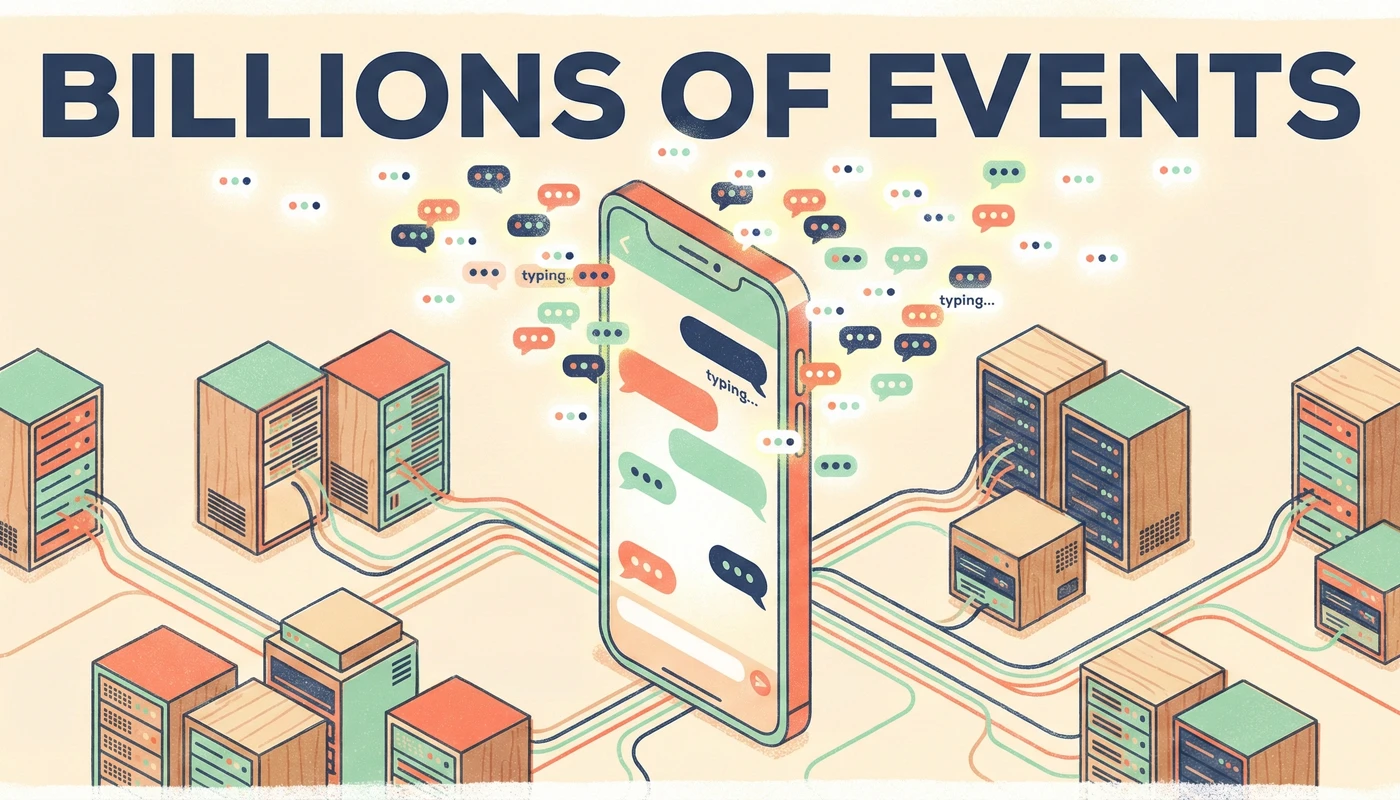

Every time you see “typing…” in WhatsApp or Slack, you’re witnessing the result of one of engineering’s most elegant optimizations. It’s not magic it’s a carefully orchestrated system that prevents billions of users from literally melting the internet with their keystrokes.

The hard truth is that most developers fundamentally misunderstand how real-time indicators work. They picture a simple loop: check the server, update the UI, repeat. At WhatsApp’s scale, that naive approach would generate roughly 2 billion HTTP requests per second just for typing status alone. Your infrastructure would crater before lunch.

Let’s dissect how the giants actually solve this, and why your implementation probably needs a rethink.

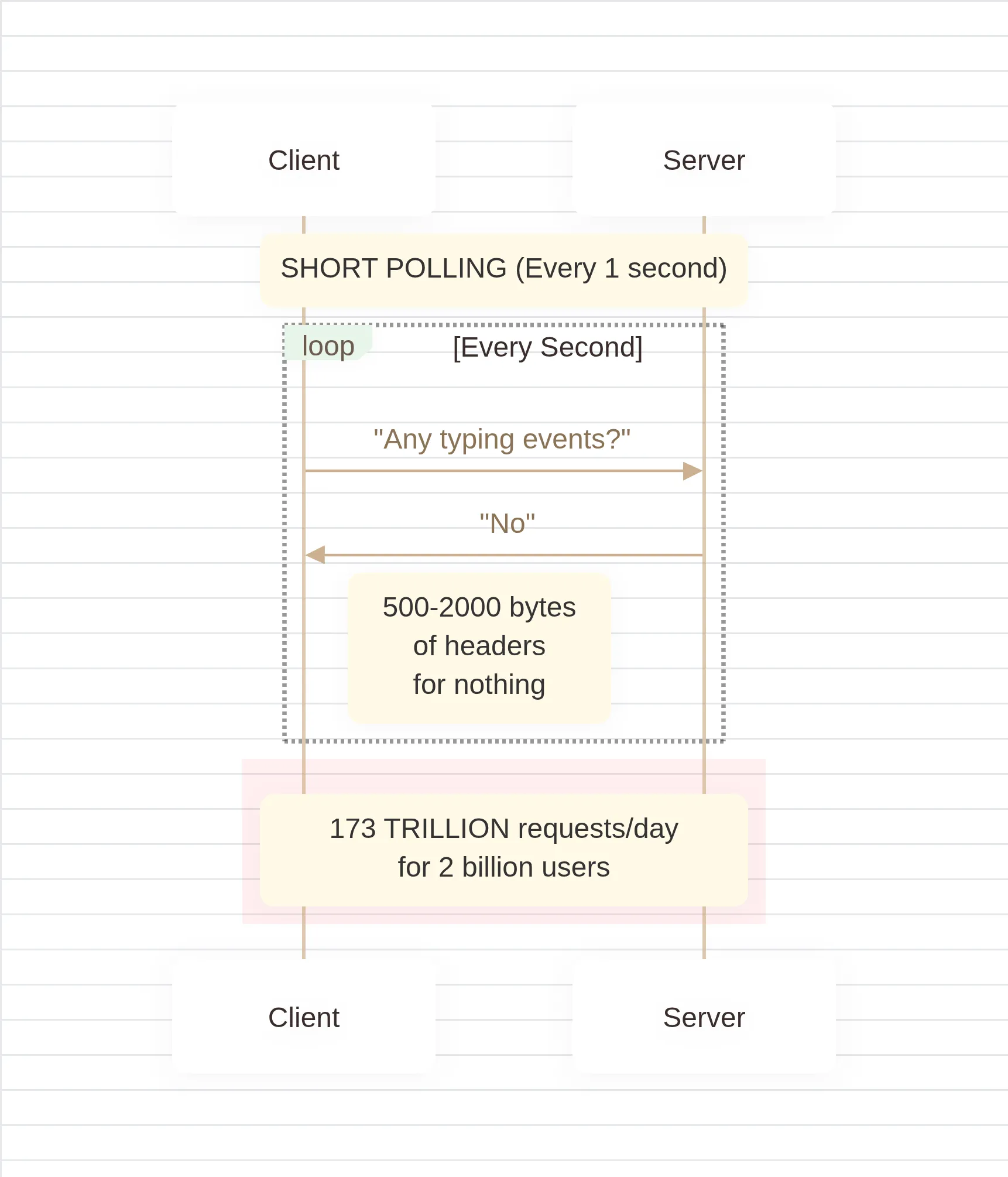

The Polling Illusion and Why It Collapses

Short polling is the default mental model for junior developers. The client asks “anything new?” every few seconds, and the server responds. Simple, stateless, and catastrophically expensive at scale.

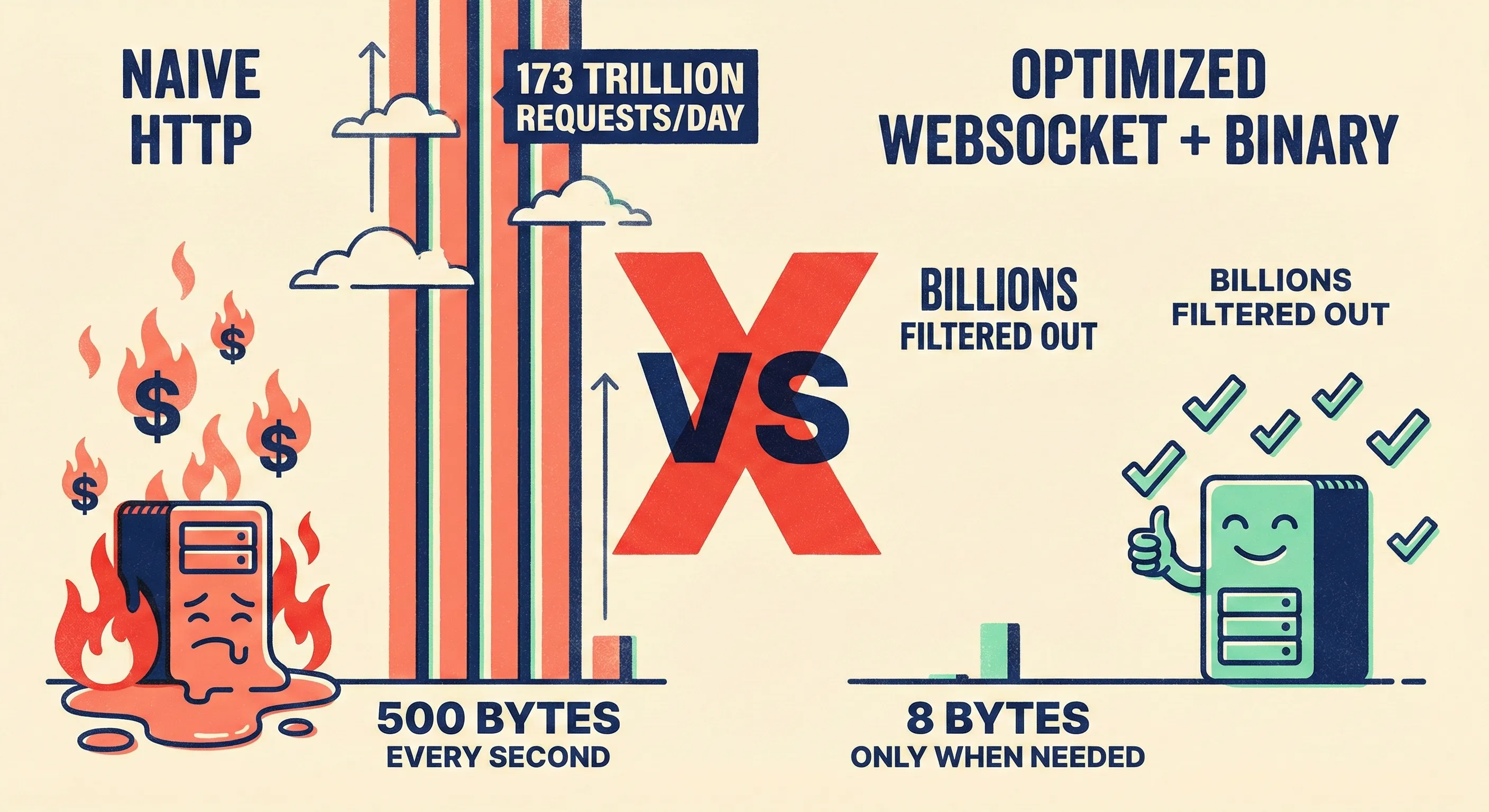

Consider the math: If WhatsApp’s 2+ billion users polled every second for typing status, that’s 173 trillion requests daily just for ephemeral UI indicators. Each HTTP request carries 500-2000 bytes of headers alone. You’re burning bandwidth on empty packets asking about nothing.

The real architecture relies on persistent bidirectional connections typically WebSockets or custom TCP implementations. WhatsApp specifically maintains a single multiplexed TCP connection per device that handles messages, receipts, presence updates, and typing indicators simultaneously. After an initial handshake, the connection stays open. The server pushes data only when events actually occur. No empty requests. No header overhead. No connection churn.

The efficiency gain is staggering. Where polling consumes bandwidth proportional to time (regardless of activity), persistent connections consume bandwidth proportional to actual events. For a quiet chat session, that’s near-zero overhead.

The Binary Event Protocol

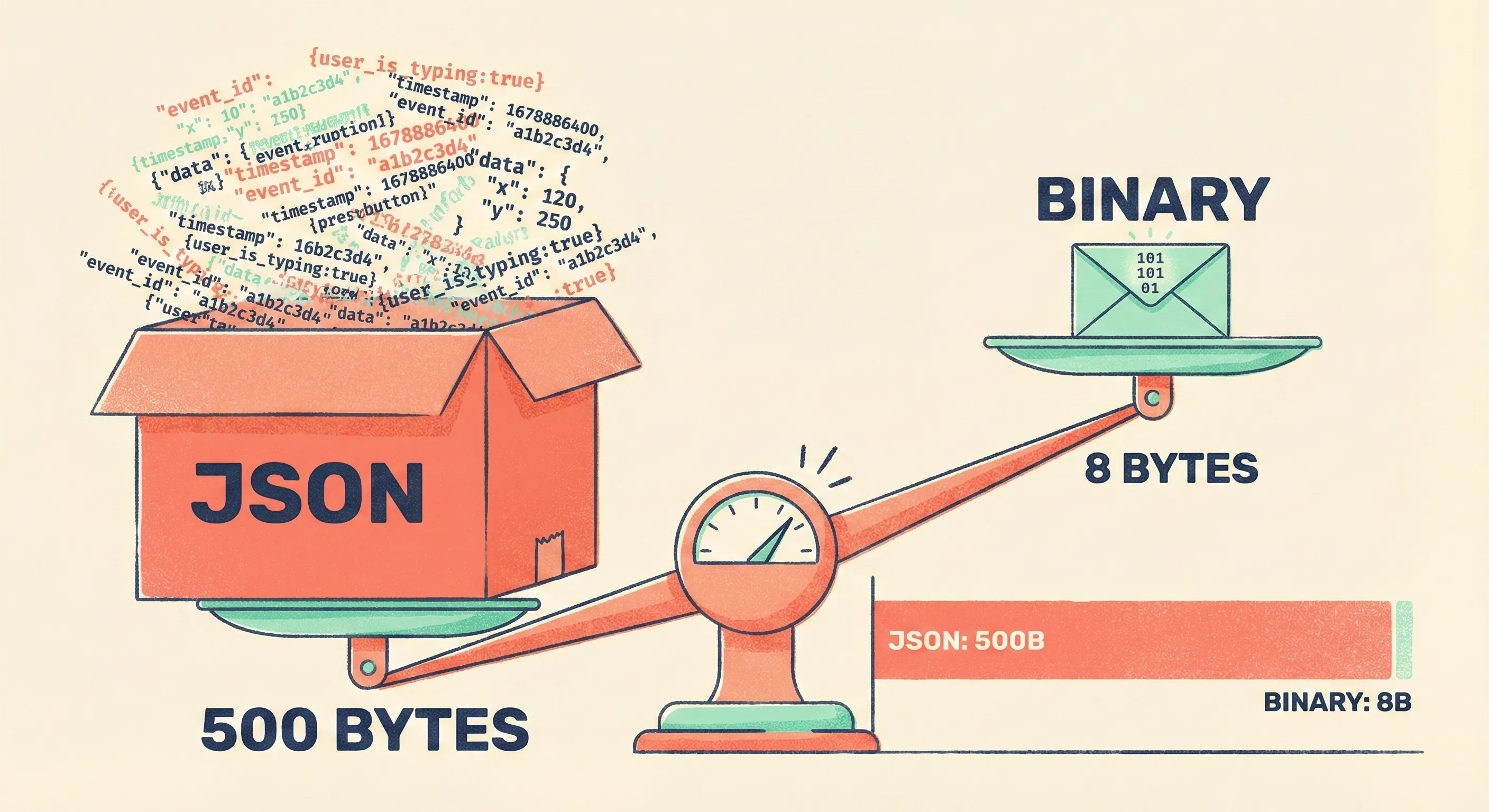

Here’s where most tutorials get it wrong. They suggest sending “User is typing” as a JSON string for every keystroke. That’s still too heavy.

WhatsApp uses binary protocol buffers tiny packets measured in single-digit bytes, not kilobytes. The typing indicator isn’t a REST API call. It’s a binary frame with an opcode, a timestamp, and a session identifier. We’re talking about 5-10 bytes flying across the wire, not 500-byte HTTP headers.

The event flow looks like this:

The event flow looks like this:

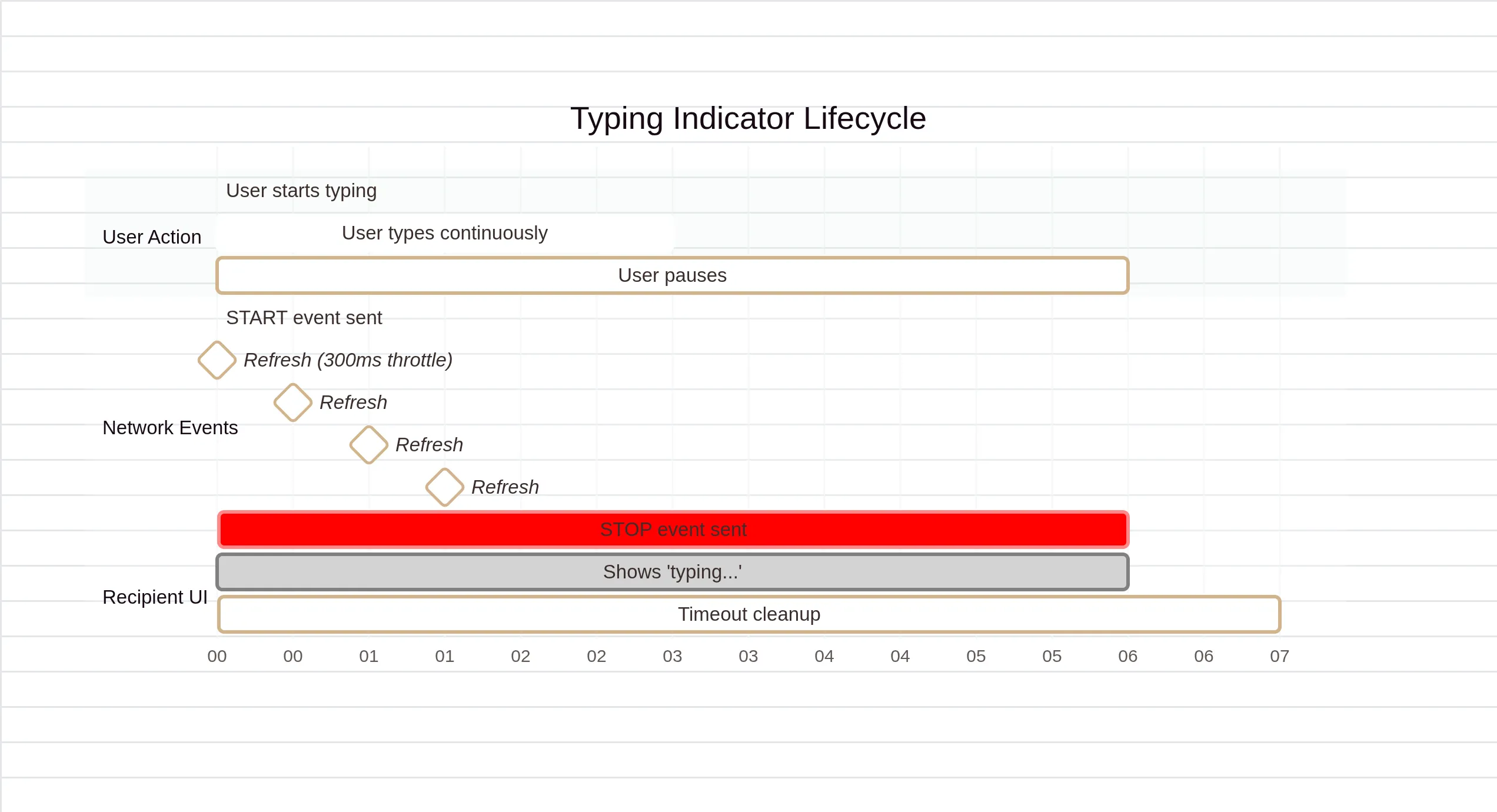

- Typing Started: A binary packet fires when the user begins input

- Typing Refresh: Periodic “still typing” signals (throttled to every 300-500ms)

- Typing Stopped: Explicit signal after inactivity, or implicit timeout on the recipient side

The recipient maintains a local timer (typically 4-6 seconds). If no refresh arrives, the UI transitions to idle automatically. This prevents stale states without requiring constant server confirmation.

The recipient maintains a local timer (typically 4-6 seconds). If no refresh arrives, the UI transitions to idle automatically. This prevents stale states without requiring constant server confirmation.

The Event Flooding Problem

Even with persistent connections, naive implementation kills you. If every keystroke triggered a network packet, typing “Hello” would generate 5 separate events. At 100 words per minute across billions of users, you create a thundering herd of micro-packets that overwhelm your presence servers.

This manifests as three distinct production failures:

This manifests as three distinct production failures:

Server Overload: Connection pools saturate handling millions of concurrent tiny writes. Your presence service the component routing these ephemeral events becomes CPU-bound on I/O operations.

Battery Annihilation: Mobile radios wake up for each packet transmission. Constant micro-transmissions keep the radio in high-power state, draining device batteries within hours. Android’s Doze mode specifically throttles apps that abuse wake-ups.

Race Conditions: Network jitter means “Stop Typing” can arrive before “Start Typing.” Without sequence handling, users see flickering indicators or stuck “typing…” states that persist indefinitely.

Throttling vs. Debouncing: The Critical Distinction

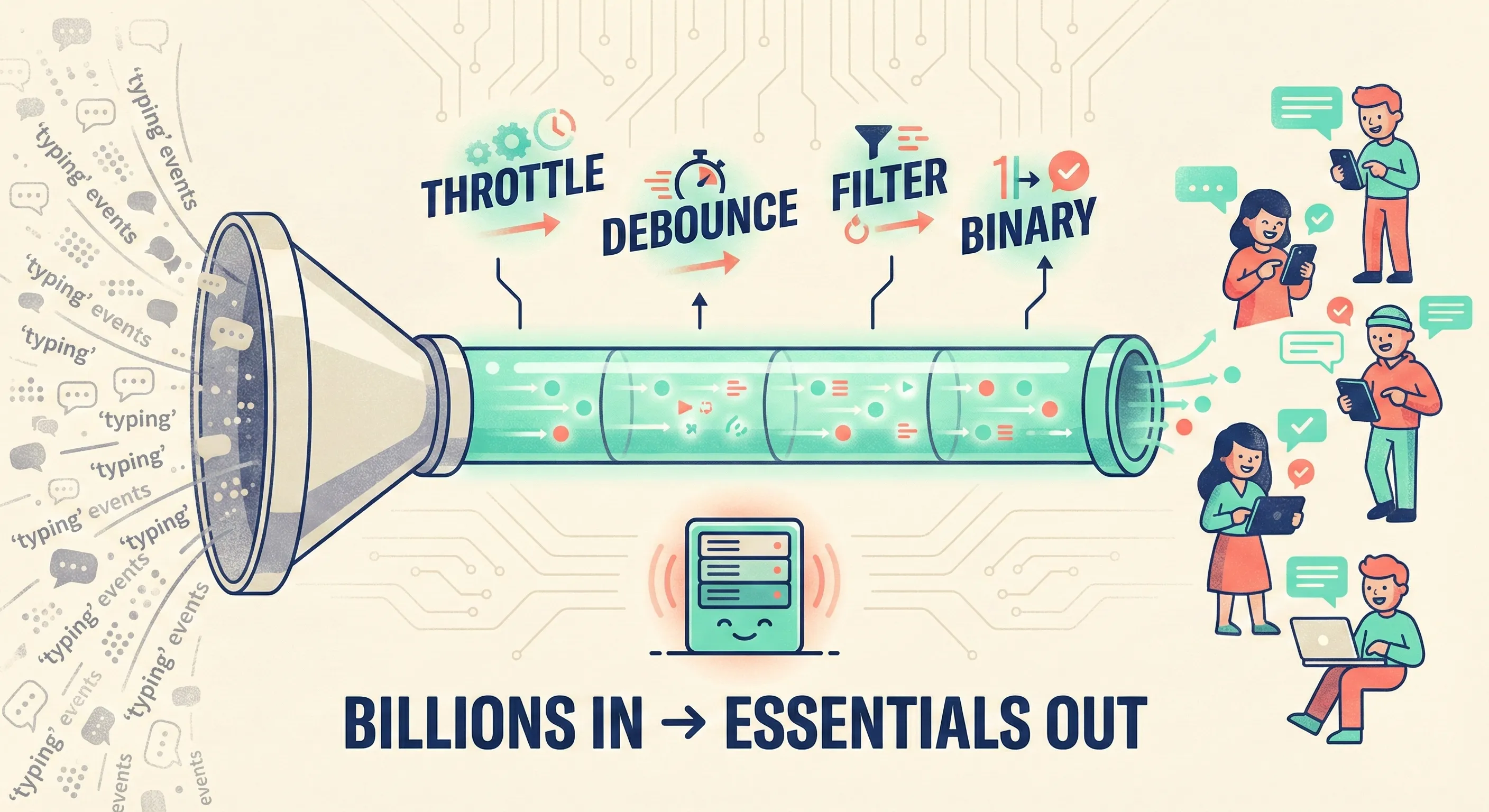

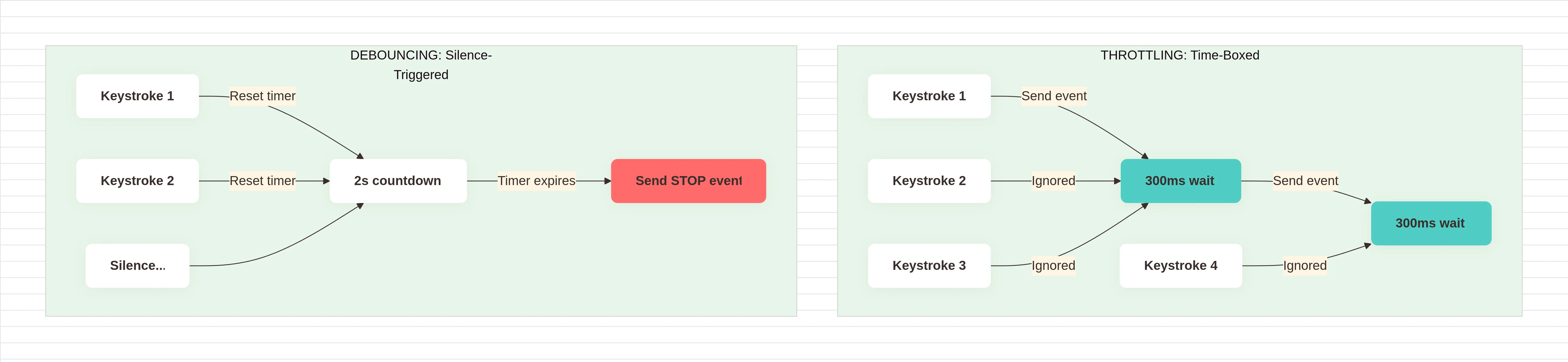

To solve flooding, engineers apply two optimization patterns often confused, but functionally distinct:

To solve flooding, engineers apply two optimization patterns often confused, but functionally distinct:

Throttling (Time-Boxed Execution)

Throttling limits function execution to once per fixed interval. If you type 100 words per minute, the client sends “Still Typing” updates every 300-500ms regardless of keystroke velocity.

Implementation logic: The client maintains a lastSent timestamp. Every keystroke checks if (now - lastSent > 300ms). If true, fire the event and reset the timer. If false, ignore.

Why it matters: It bounds your network traffic. Even if a user mashes keys at 1000 WPM, you never exceed 3-4 packets per second. Your server load becomes predictable and constant, not proportional to typing speed.

Debouncing (Silence-Triggered Execution)

Debouncing waits for a period of inactivity before executing. For typing indicators, this determines when to send the “Stopped Typing” signal.

Implementation logic: Each keystroke resets a 2-second timer. Only when the timer expires without new input does the client emit the stop event.

Why it matters: It prevents premature “stopped” signals during pauses. Users often pause mid-thought; debouncing distinguishes between “finished typing” and “thinking.”

The combination is surgical: Throttling manages active typing traffic, while debouncing handles the transition to idle. Together, they compress billions of potential events into manageable, predictable traffic patterns.

Server-Side Presence Routing

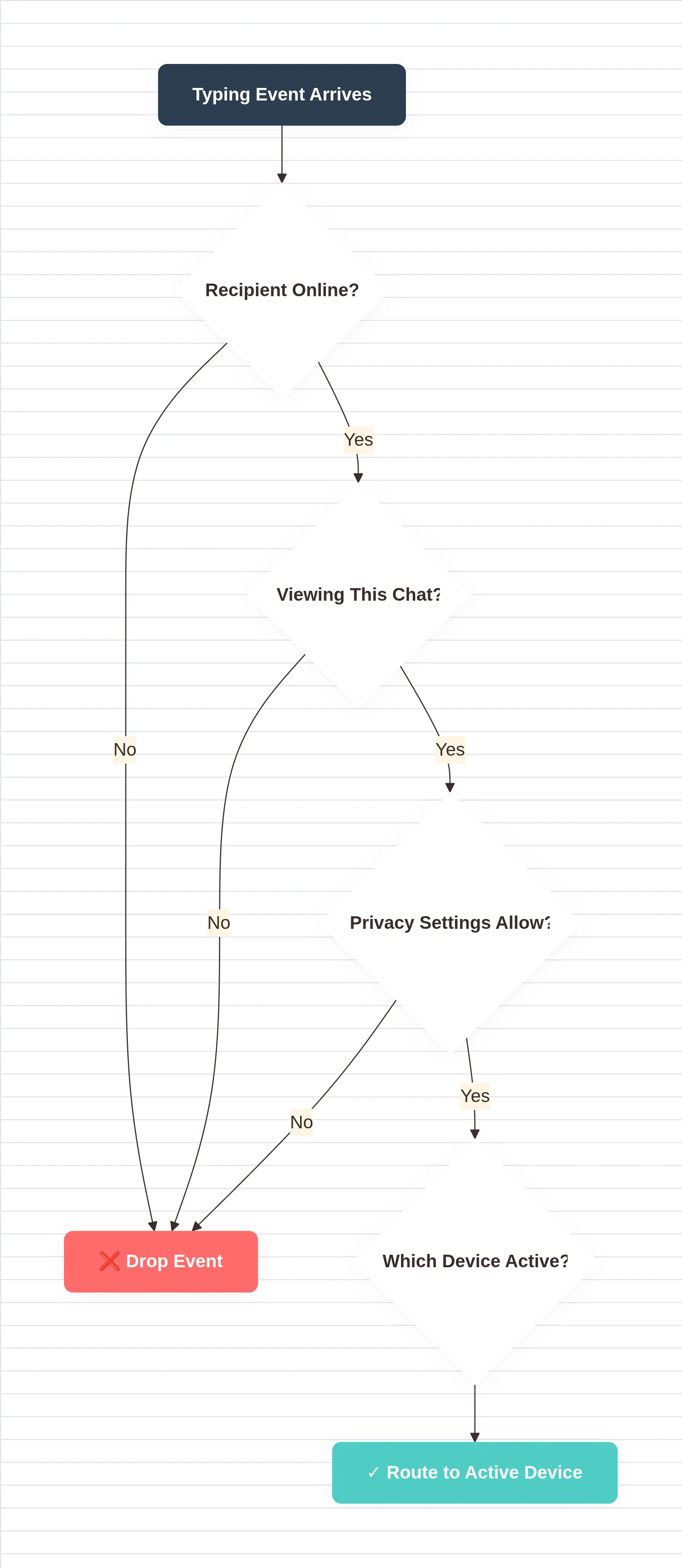

When that throttled packet reaches WhatsApp’s servers, it doesn’t broadcast to the world. It hits a Presence Distributor that applies privacy and relevance filters:

- Online Status Check: Is the recipient actually connected? If offline, the event dies here no wasted bandwidth.

- Chat Context Verification: Is the recipient currently viewing this specific conversation? Typing indicators only route to active chat windows.

- Privacy Settings: Has the user disabled read receipts or presence sharing? The system respects these flags at the routing layer, not the client.

- Multi-Device Coordination: If User B has three devices, which ones get the indicator? Usually only the active session.

This routing layer prevents the “fan-out” problem where one typing event spams all of a user’s contacts. The system maintains a graph of active sessions and routes events only to relevant edges.

This routing layer prevents the “fan-out” problem where one typing event spams all of a user’s contacts. The system maintains a graph of active sessions and routes events only to relevant edges.

The Infrastructure Reality Check

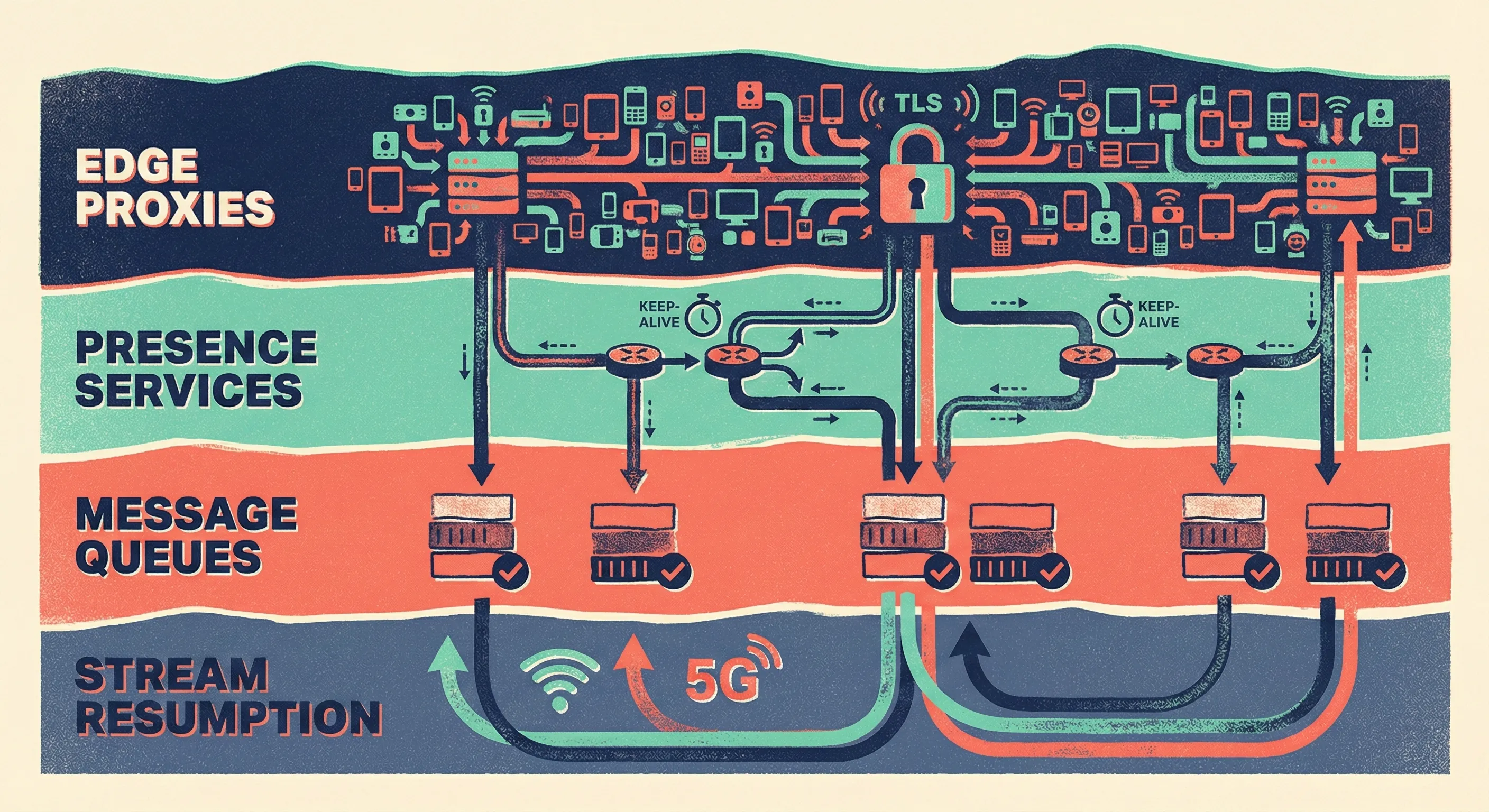

Meta’s infrastructure handles this through a hierarchy of services:

- Edge Proxies: Terminate millions of WebSocket connections, handling TLS and keep-alive logic

- Presence Services: Stateful servers tracking who’s online and where, routing ephemeral events

- Message Queues: Buffering and ordering guarantees for non-ephemeral messages

- Stream Resumption: Handling mobile network drops without losing state when your phone switches from WiFi to 5G, the connection resumes without re-authentication

The key insight: Typing indicators are treated as ephemeral, best-effort signals, not guaranteed delivery messages. If a “typing” packet drops, the world doesn’t end. The recipient’s local timeout handles the cleanup. This relaxed consistency model allows the system to prioritize speed over durability.

The key insight: Typing indicators are treated as ephemeral, best-effort signals, not guaranteed delivery messages. If a “typing” packet drops, the world doesn’t end. The recipient’s local timeout handles the cleanup. This relaxed consistency model allows the system to prioritize speed over durability.

Implementation Checklist for Your Stack

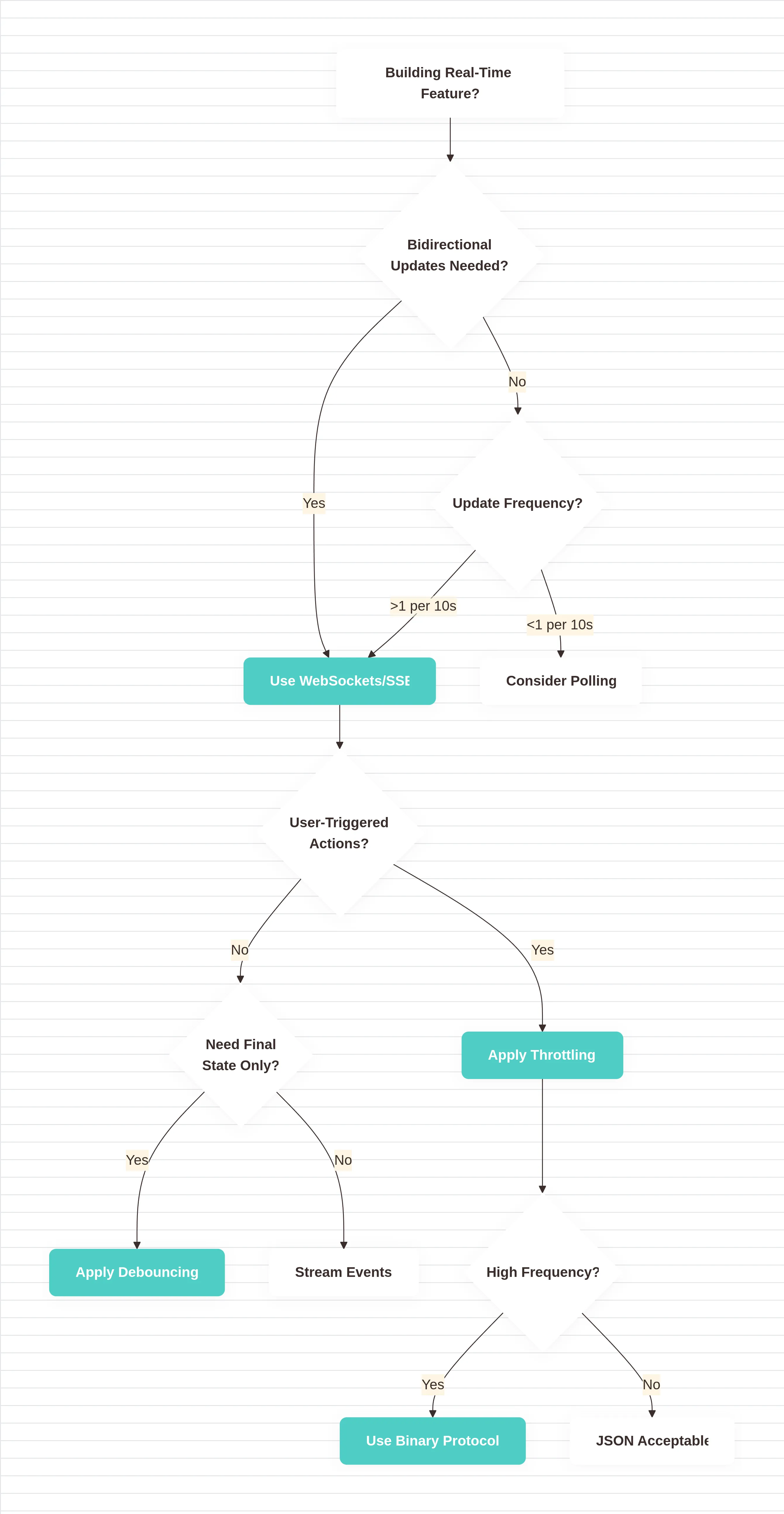

If you’re building real-time features, here’s the decision tree:

If you’re building real-time features, here’s the decision tree:

Use persistent connections (WebSockets/SSE) for:

- Bidirectional real-time requirements

- High-frequency updates (>1 per 10 seconds)

- Battery-sensitive mobile applications

Apply throttling when:

- User actions trigger network calls

- You need predictable server load

- Input frequency varies wildly (typing, scrolling, resizing)

Apply debouncing when:

- You care about the “final” state, not intermediate steps

- Actions have natural completion points (search input, form fields)

- You want to avoid “in-progress” noise

Never send JSON over WebSockets for high-frequency events. Use binary protocols (MessagePack, Protocol Buffers, or raw binary frames). The overhead difference between 500 bytes of JSON and 10 bytes of binary is the difference between scaling to millions and collapsing at thousands.

The Bottom Line

The Bottom Line

The “typing…” indicator is a microcosm of distributed systems engineering. It looks simple because the complexity is buried: binary protocols, throttled emissions, presence routing, and graceful degradation.

WhatsApp doesn’t handle billions of typing events by buying more servers. They handle it by not handling most events aggressively filtering, throttling, and dropping packets that don’t matter. The art is knowing which packets to keep.

If your real-time implementation sends HTTP requests for every keystroke, you’re not building a chat app. You’re building a distributed denial-of-service attack against your own infrastructure.