The Real Problem

You deploy the new micro-frontend, open the browser, and the call to GET /api/user dies with:

Access to fetch at 'https://api.x.com/user' from origin 'https://app.x.com'

has been blocked by CORS policyThe ticket lands on your board labeled “API broken”. You add the wildcard header, push, close the ticket. Three weeks later a security audit flags the same endpoint for over-permissive access and you are back in the code, only now you also have to explain to finance why the pen-test is repeating.

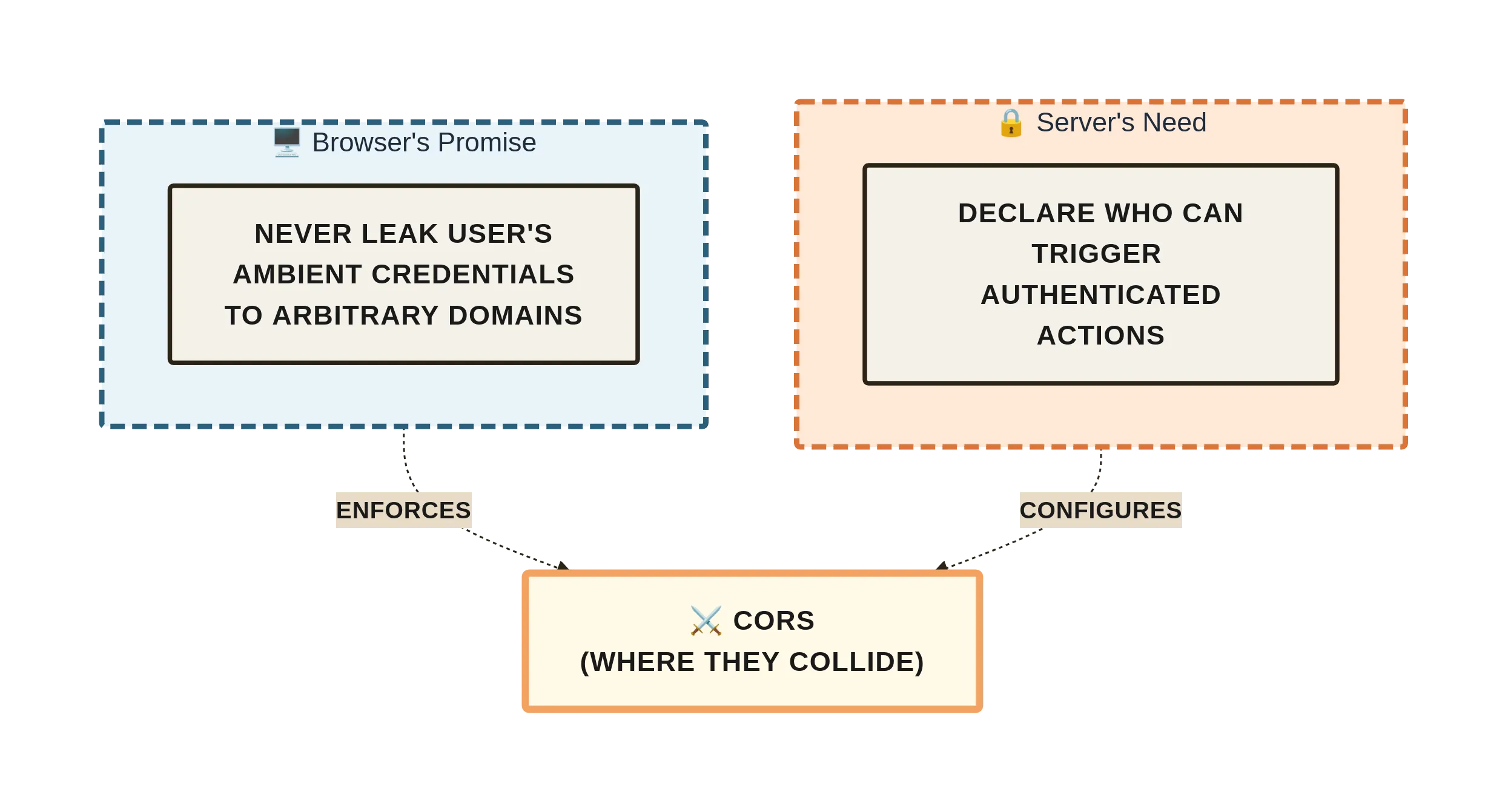

What looked like a one-line nuisance is actually a design conflict between two guarantees the web stack tries to give:

- A server must be able to declare who can trigger authenticated actions on it.

- A browser must never leak the user’s ambient credentials (cookies, basic auth, client certs) to an arbitrary domain.

CORS is where those guarantees collide. Most “fixes” silence the symptom without understanding which guarantee is being sacrificed, so the problem re-appears in a different costume—sometimes as a security incident, sometimes as a hard-to-reproduce cache mismatch, sometimes as a sudden spike in preflight traffic that triples your bill.

What Most Explanations Miss

Blog posts usually stop at “Add Access-Control-Allow-Origin:* and move on.” They do not mention:

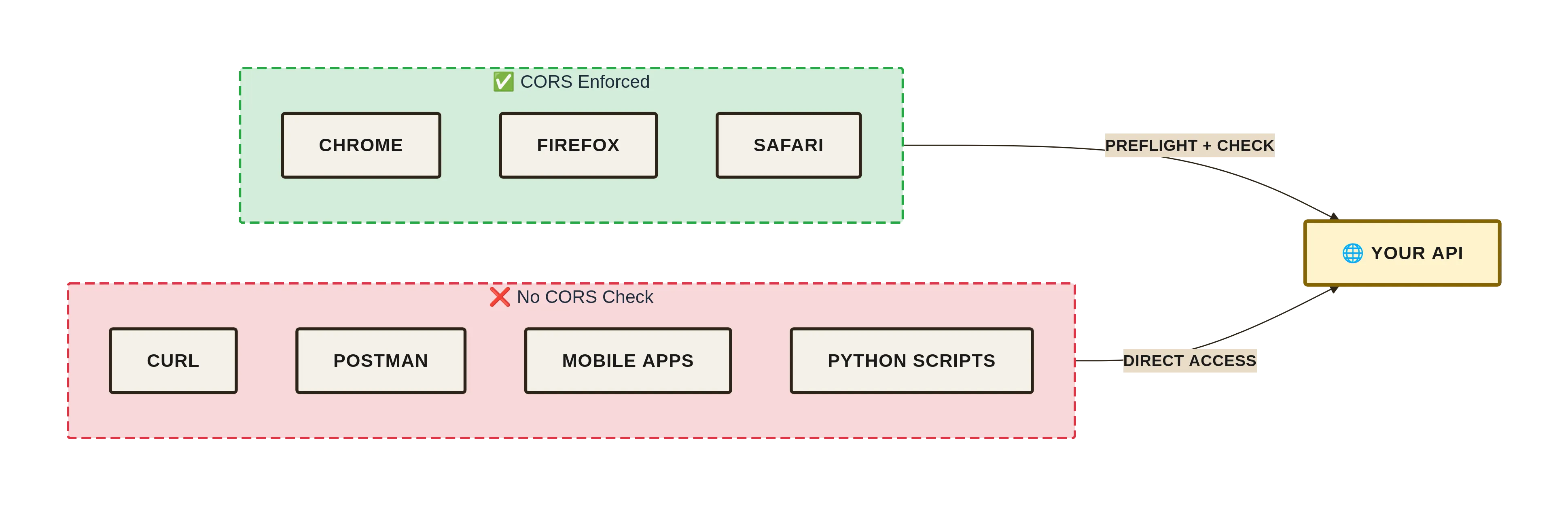

- CORS is enforced only by browsers. Curl, Postman, your mobile app, and the attacker’s python script never perform the preflight check.

- The preflight is not a server-side security gate; it is a client-side consent screen. The server still has to authenticate every request.

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: trueandAccess-Control-Allow-Origin:*are mutually exclusive. Combine them and every browser silently downgrades to a same-origin request, leaving developers convinced the header is “ignored”.- Caching proxies cache the preflight OPTIONS response. A careless

max-age=86400can propagate a temporary whitelist typo for a day. - The spec distinguishes between “simple” and “non-simple” requests. That distinction decides whether the browser fires one or two round-trips. Performance budgets frequently ignore the second trip until latency climbs after launch.

How It Actually Works

1. Origin Comparison (Exact String Match)

Origin = scheme + host + portNo normalisation, no sub-domain inheritance, no “https is close enough”. https://shop.example.com:443 is different from https://shop.example.com because the port is explicit in the first.

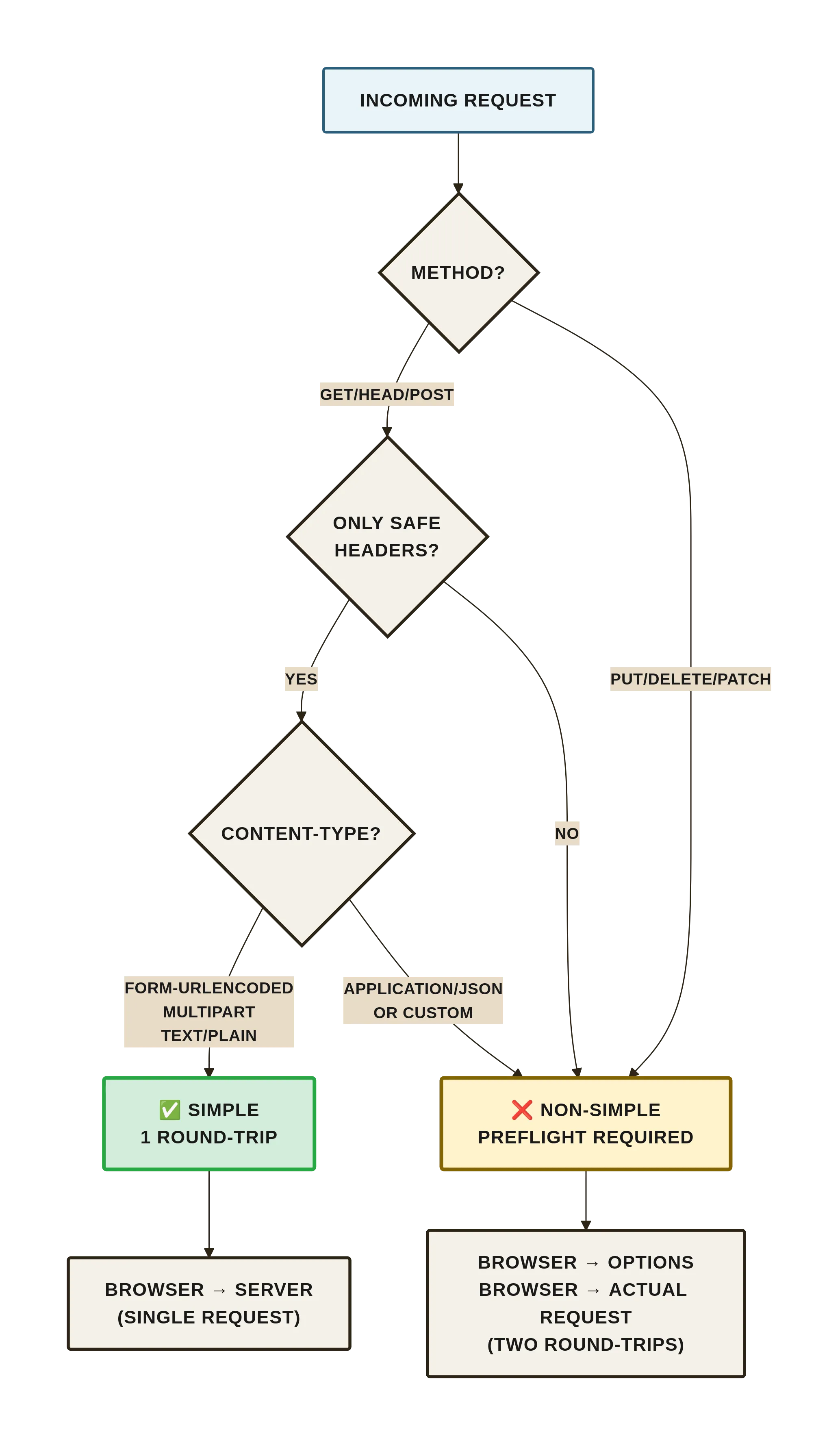

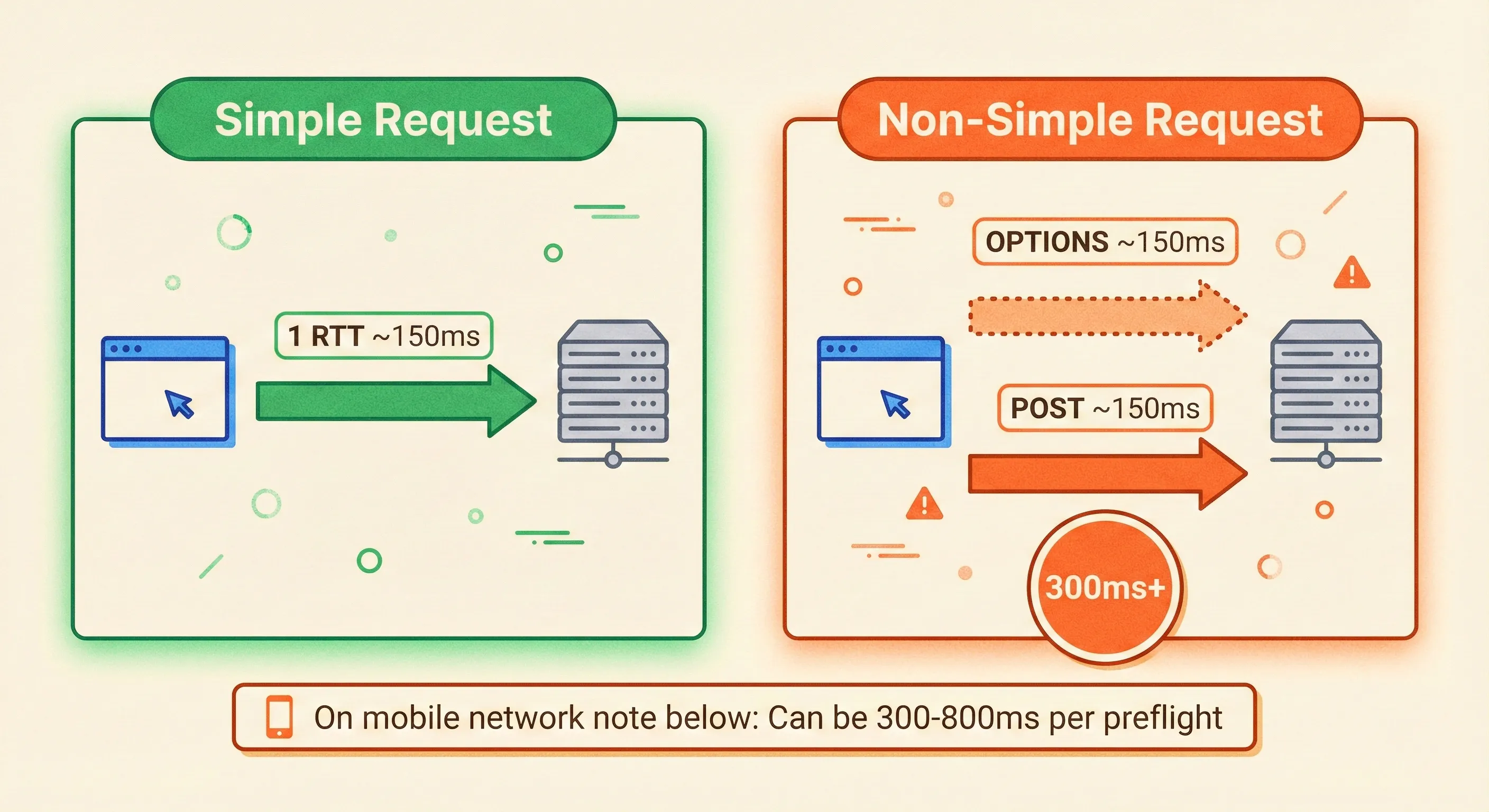

2. Simple vs. Non-Simple (The 1RTT vs. 2RTT Split)

A request is simple only when all of these hold:

- Method: GET, HEAD, or POST

- Headers: no manually set headers except the safelist (

accept,accept-language,content-language,content-type) - Content-Type:

application/x-www-form-urlencoded,multipart/form-data, ortext/plain

Everything else—application/json, authorization, custom headers—triggers a preflight.

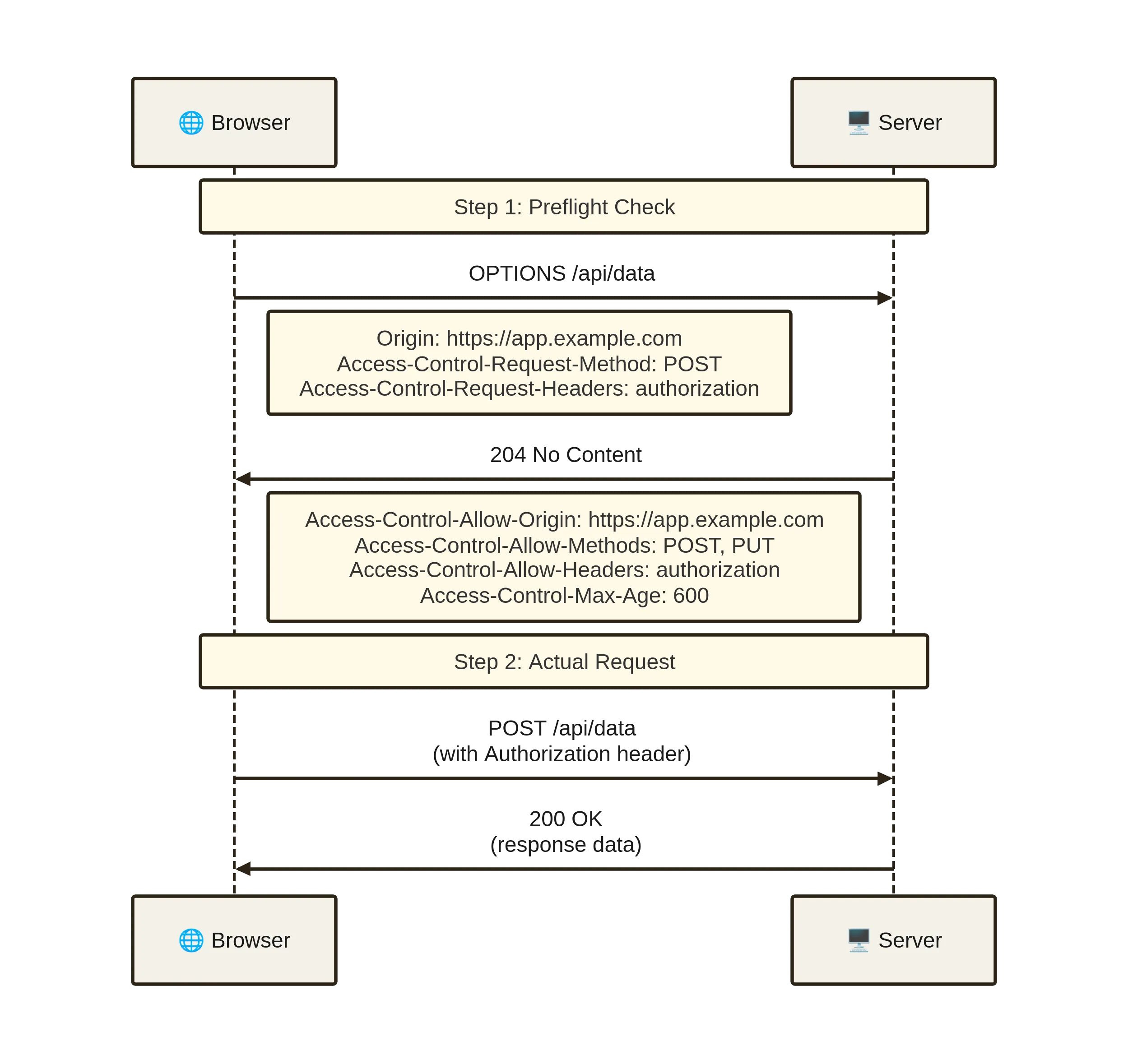

3. Preflow Sequence (Two Round-Trips)

Browser → OPTIONS /api/data

Origin: https://app.example.com

Access-Control-Request-Method: POST

Access-Control-Request-Headers: content-type,authorization

Server → 204 No Content

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://app.example.com

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: POST, PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: content-type,authorization

Access-Control-Max-Age: 600

Browser → POST /api/data …If any header or method is absent from the server reply, the browser aborts before your application code runs. No fetch rejection handler will see the actual response body because the browser never exposes it.

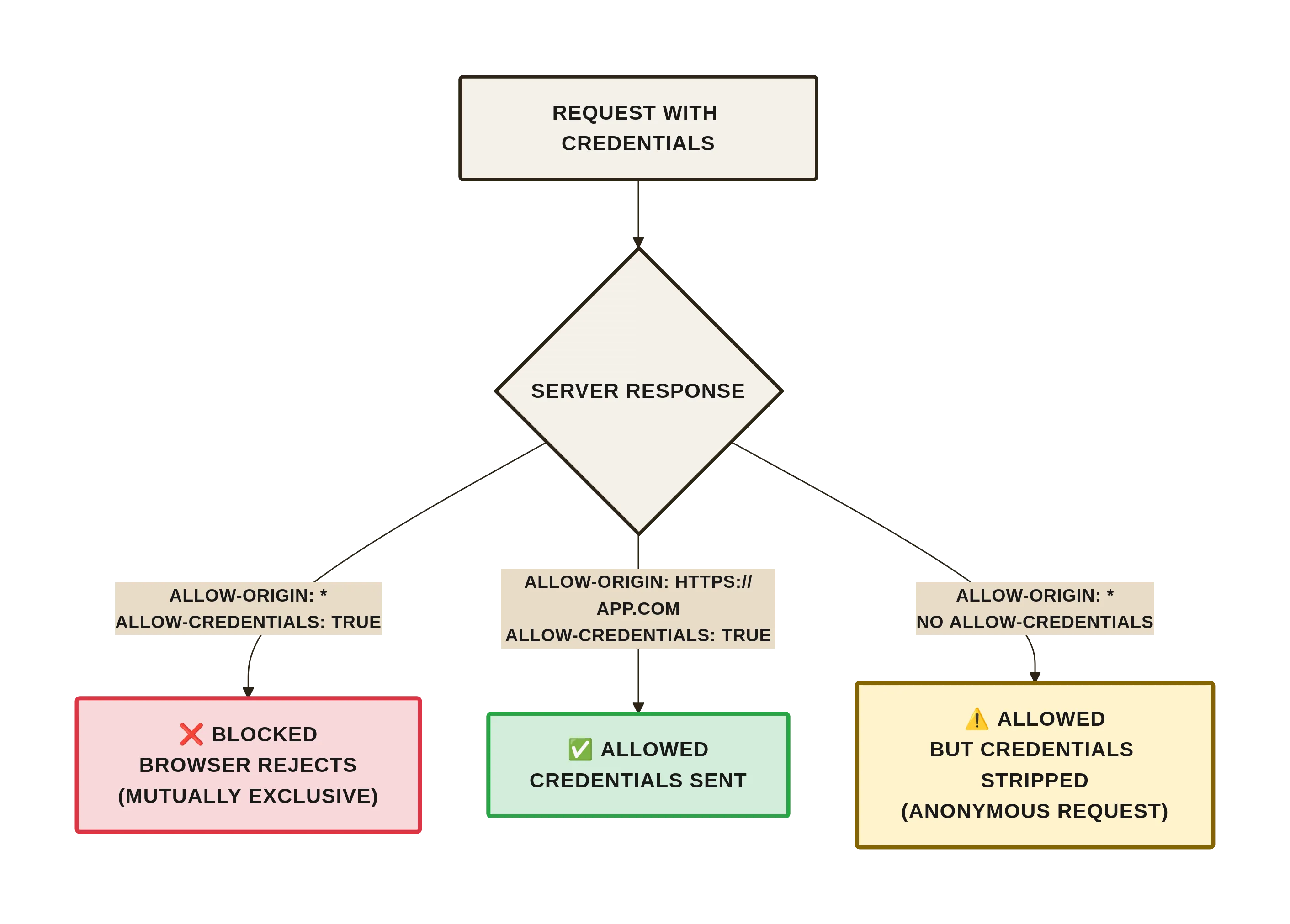

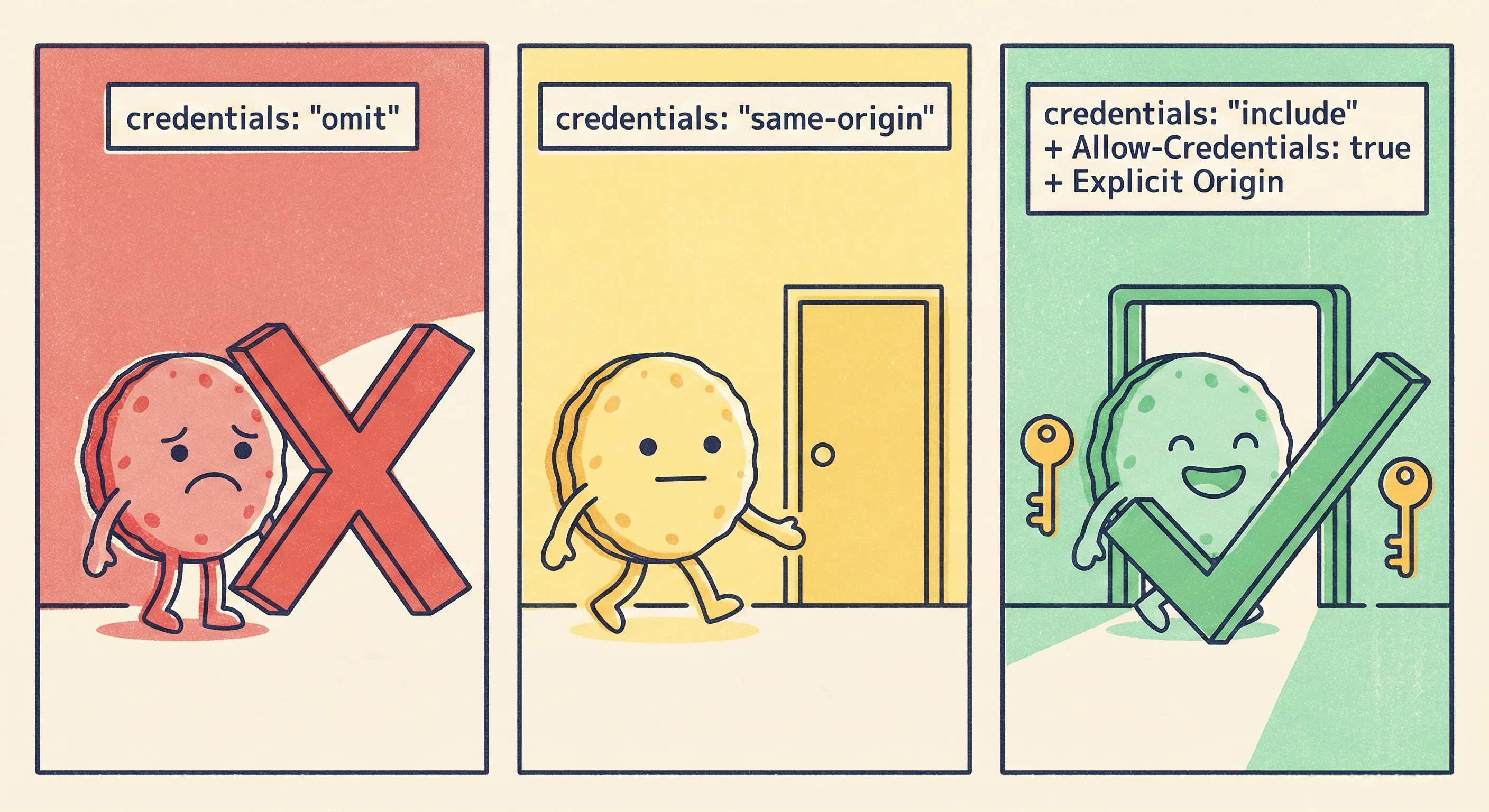

4. Credential Inclusion (The Third State)

Cookies, HTTP basic, or client certs are sent only when:

- Fetch is called with

credentials:'include'/ XHR withwithCredentials=true - Server responds with

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: trueand an explicit origin (*is invalid here)

Miss either and the browser strips credentials, turning what you thought was an authenticated call into an anonymous one. Most “CORS works in dev, fails in prod” stories trace back to this mismatch.

Trade-offs and Constraints

What You Gain

- You can keep the browser’s ambient credentials while calling APIs on a different subdomain.

- You can operate a public API that rejects browser-based CSRF without writing custom tokens.

- You can version frontends independently of backends because the same API can whitelist multiple origins.

What You Lose

- One extra hop for every non-simple request. On mobile networks that can be 300–800 ms.

- Cache semantics become complicated: preflight responses are not heuristic-cacheable, so CDNs must be explicitly configured.

- You expose your whitelist to anyone who can read response headers—no secret sauce.

- Debugging is browser-specific; dev tools do not show the OPTIONS failure until you open the network tab and replay, which makes post-mortems painful.

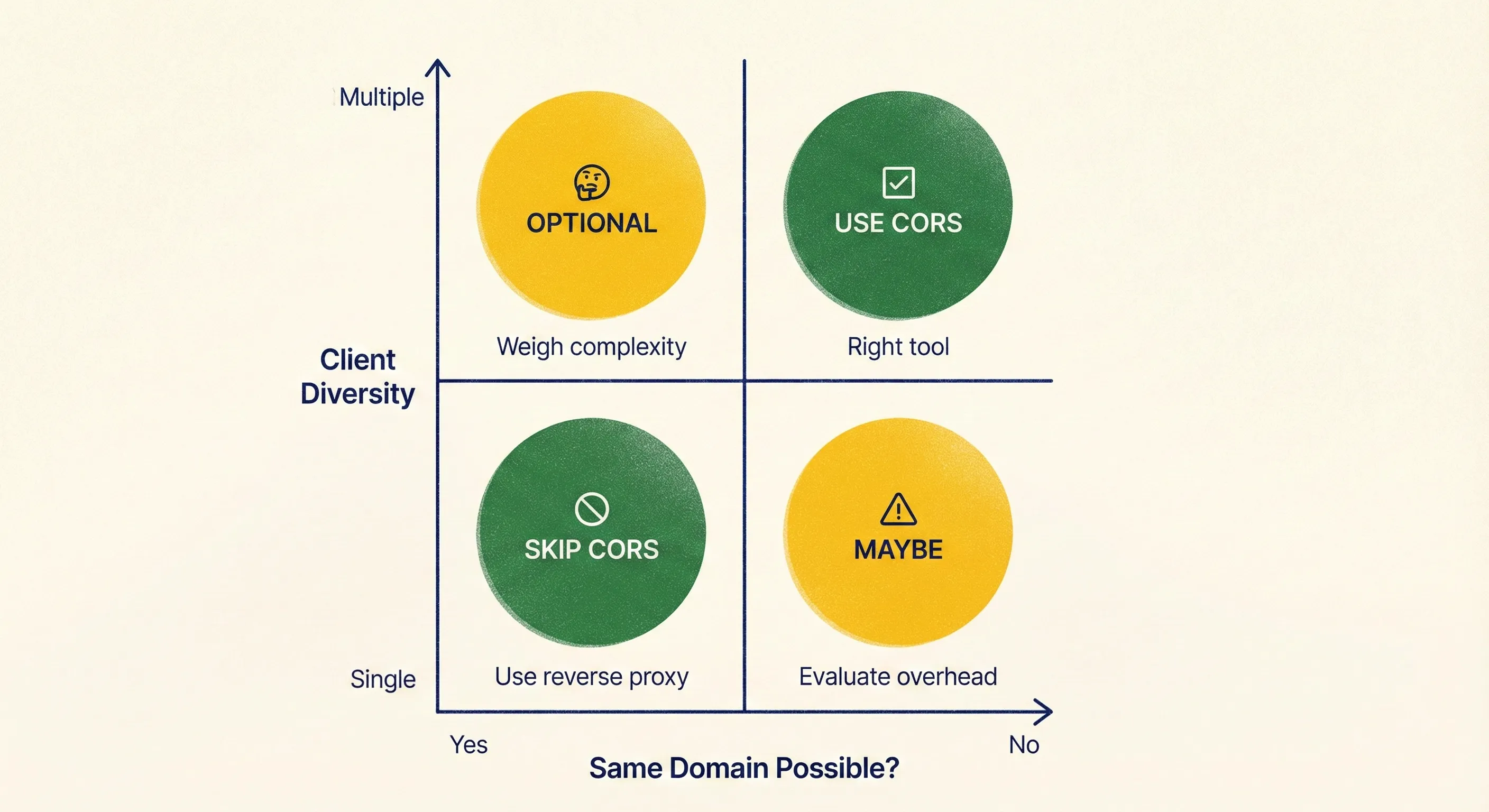

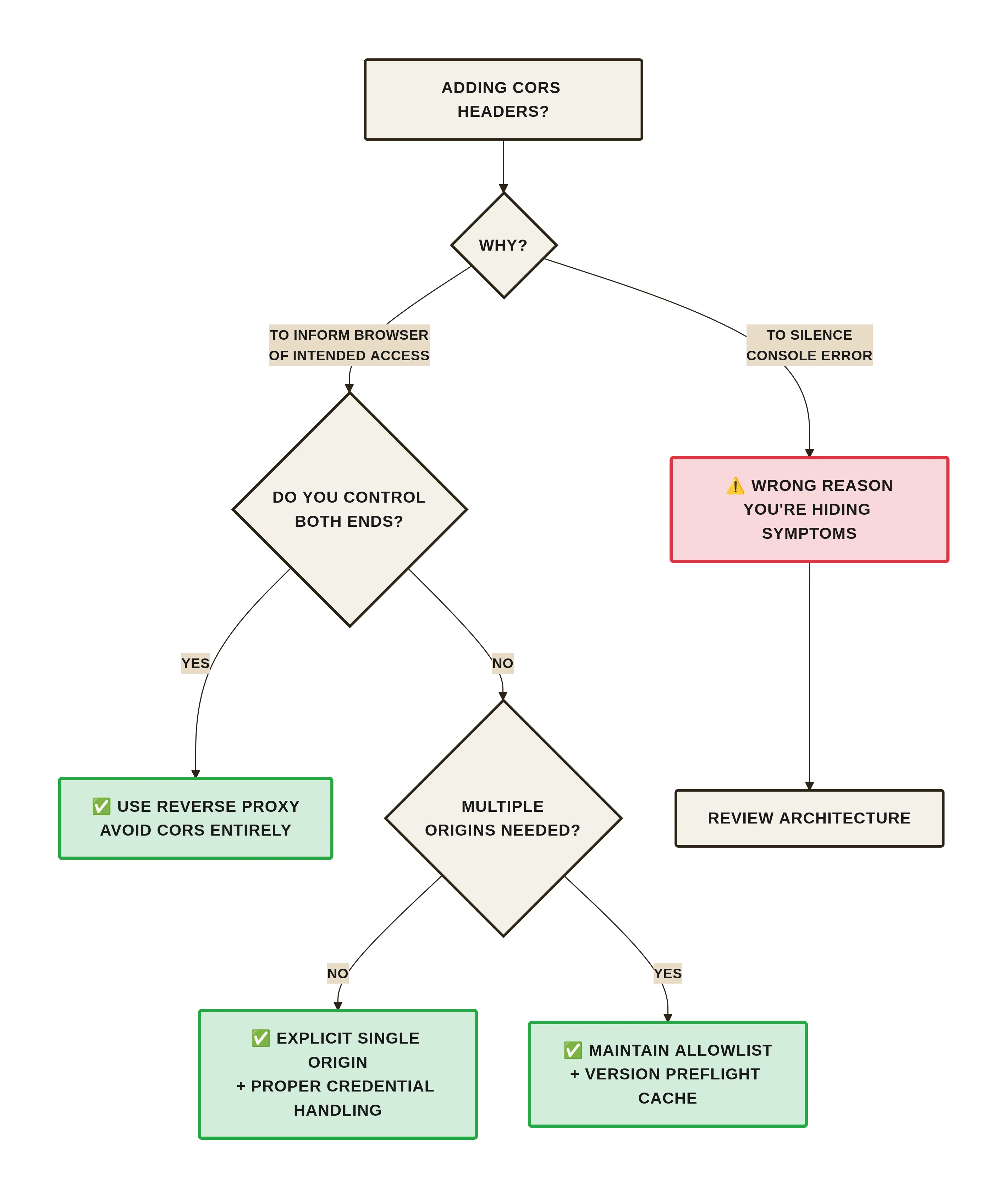

When This Is a Bad Idea

- You control both ends and could run them under the same registrable domain—use a reverse proxy and avoid CORS entirely.

- Your API is meant for non-browser clients only; CORS adds no value but still invites misconfiguration.

- You need to support very old embedded browsers (IE11 and friends) whose preflight implementation is buggy; you will spend more time on polyfills than on features.

Practical Insights

- Treat

Access-Control-Allow-Originlike a firewall rule, not a string patch.- Keep an allowlist array in config, never hard-code.

- Reject with 403 instead of reflecting arbitrary

Originheaders; reflection is an open redirect in disguise.

- Version your preflight cache.

- Include a build ID in

Access-Control-Max-Ageso emergency rollbacks do not have to wait out the TTL. - Default to 5 min in production; increase only when you measure preflight volume.

- Include a build ID in

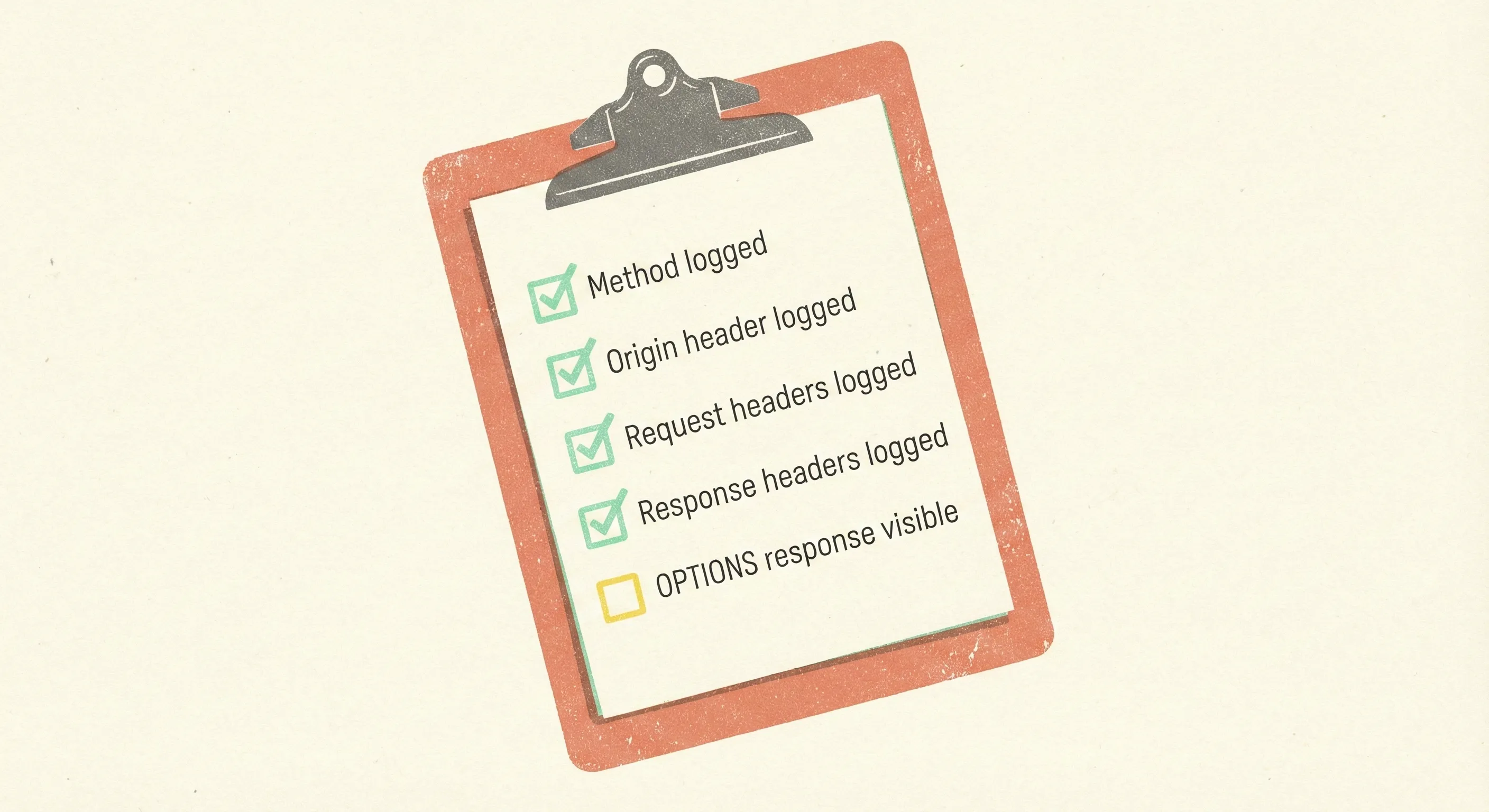

- Log the entire CORS conversation during incidents.

- Most loggers skip OPTIONS because it has no body. Log method, origin, request-headers, and response headers; they are the only evidence when a mobile release changes its fetch defaults.

- Most loggers skip OPTIONS because it has no body. Log method, origin, request-headers, and response headers; they are the only evidence when a mobile release changes its fetch defaults.

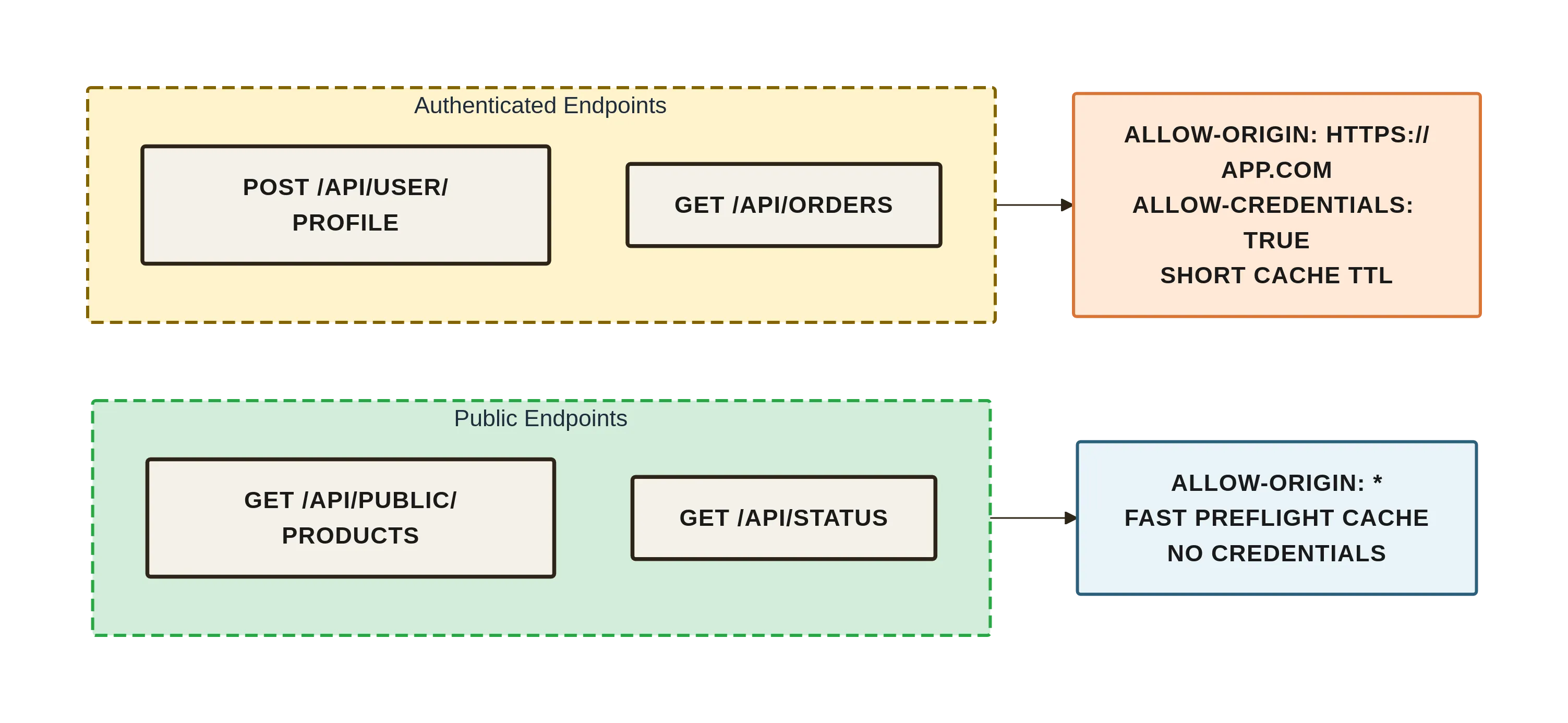

- Separate “public” and “authenticated” endpoints at the DNS or path level.

- Public endpoints can use

*safely, keeping caches simple. - Authenticated endpoints get their own subdomain and a short, explicit allowlist—reducing the chance you will mix credentials into a wildcard.

- Public endpoints can use

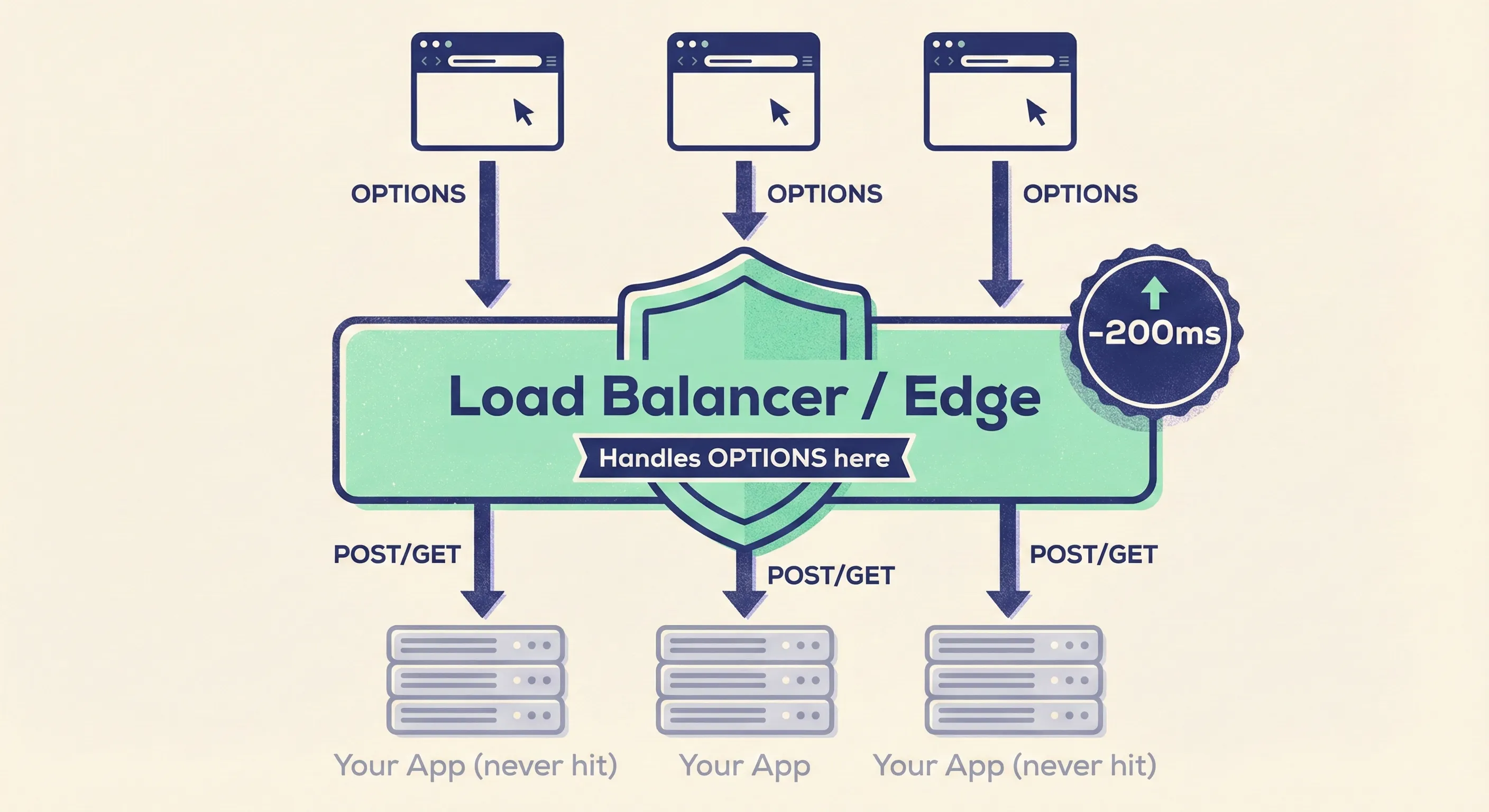

- Load balancers can answer preflights without hitting your app.

- Nginx map directive or Envoy Cors filter can shave entire milliseconds off latency and protect your origin from preflight thundering herd during traffic spikes.

- Nginx map directive or Envoy Cors filter can shave entire milliseconds off latency and protect your origin from preflight thundering herd during traffic spikes.

- Do not wrap every route with a CORS middleware that re-evaluates the allowlist.

- Preflight is an edge concern; handle it in the outermost layer and short-circuit so your business middleware stack never spins up.

Closing Thought

If you find yourself adding CORS headers to make an error go away, pause and decide whether you are relaxing the browser’s CSRF protection or merely informing it. The right header is the one that makes the protection true, not the one that makes the console quiet.